The John Snow Society aims to promote the life and works of Dr John Snow, a pioneer of modern epidemiological method and celebrated anaesthetist.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!As outlined in the Constitution, the Society has a serious intent, publishing news, collecting facts and dates related to the life and works of John Snow and organising the Annual Pumphandle Lecture Series, but it also aims to provide a communication network for epidemiologists and those trained in the Snow tradition throughout the world.

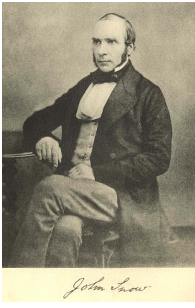

About John Snow

Dr John Snow (1813-1858) was a famous physician, widely recognised as a leader in the development of anaesthesia in Britain, as well as a pioneer of modern epidemiological methods.

Key biographical and other points about John Snow’s life and works:

- John Snow was born in York on 15 March 1813, the eldest son of a farmer. He died in London on 16 June 1858, aged 45

- His first piece of scientific work was on the use of Arsenic in the preservation of bodies (this work was abandoned due to the toxic effects on the medical students)

- From his studies in toxicology, John Snow developed an interest in anaesthesia and cholera (hence his theory on the transmission of the cholera ‘poison’ in water supplies)

- John Snow was a vegetarian and a teetotaller who campaigned for temperance societies (though he drank a little wine in later life). He first encountered a cholera epidemic in Newcastle in 1831-32 when he was sent there by the surgeon to whom he was apprenticed at the time

- It was reported that John Snow was a poor speaker with a husky voice; “always spoke to the point but found it difficult to obtain a favourable notice” (Richardson)

- John Snow occupied three properties during his time in London; 11 Batemans Buildings, Soho Square (1836-1838); 54 Frith Street, Soho Square (1838-1853); 18 Sackville Street (1853-1858)

- On 16 October 1841 John Snow presented his first paper entitled Asphyxia and the resuscitation of new-born children

- In 1846, John Snow heard about the use of anaesthesia in the USA. It was not well-received in the UK initially, due to the mode of administration but John Snow spotted how to improve this.

- In 1849, John Snow published the first edition of his best-known work On the mode of communication of cholera. It cost him £200 to produce but his income was only £3.12s

- Journals dismissed Snow’s book. “There is, in our view, an entire failure of proof that the occurrence of any one case could be clearly and unambiguously assigned to water”. The reviewer later concludes, “Notwithstanding our opinion that Dr Snow has failed in proving that cholera is communicated in the mode in which he supposes it to be, he deserves the thanks of the profession for endeavouring to solve the mystery. It is only by close analysis of facts and the publication of new views, that we can hope to arrive at the truth”. (London Medical Gazette, 1849)

- On 7 April 1853, John Snow administered obstetric anaesthesia to Queen Victoria on the birth of Prince Leopold, and again on the birth of Princess Beatrice (14 April 1857)

- John Snow beat William Budd to the water theory of transmission of cholera by only 10 days. However, although Budd’s thesis was based on more thorough surveys of rural outbreaks, he made the mistake of proposing a fungal cause

- John Snow’s views were still not accepted in Germany at the time of the Gelsenkirche Typhoid Epidemic, in 1901.

Accounts of the 1854 cholera epidemic:

- Peter Vinten-Johansen. Investigating Cholera in Broad Street: a history in documents. Broadview Press: 2020.

- Sandra Hempel. The Medical Detective: John Snow; Cholera and the Mystery of the Broad St. Pump. London Granta Books, 2006.

- Deborah Hopkinson. The Great Trouble. Subtitled ‘A mystery of London, the blue death and a boy called Eel’. Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2013.

- Steven Johnson. The Ghost Map: A Street, an Epidemic and the Hidden Power of Urban Networks. Penguin Books, 2008.

- Katherine Tansley. The Doctor of Broad Street: A Victorian Tale of Murder and Malady. Matador, 2016.

- Richard Streeter. Eliza Reid (1841–54)”—a genealogical and historical narrative of one of the earliest victims of the St. James, Westminster cholera outbreak., 2019.

Other accounts of John Snow

- Peter Vinten-Johansen, Howard Brody, Nigel Paneth, Stephen Rachman and Michael Rip. Cholera, Chloroform and the Science of Medicine: A Life of John Snow. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. (This is the most serious biography of Snow with excellent discussion of Snow’s life and his work on anaesthetics, cholera and maps – the corresponding webpage is The John Snow archive and research companion)

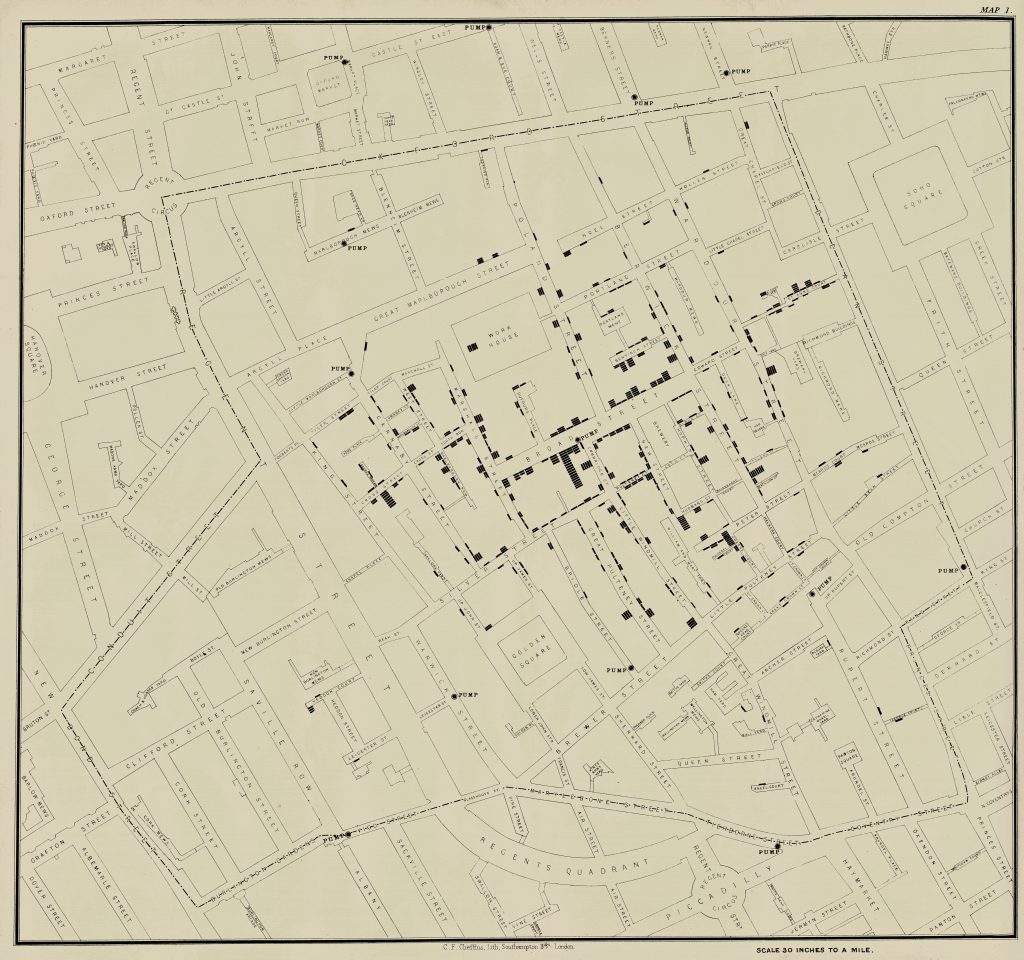

- The University of California Department of Epidemiolgy have a website dedicated to John Snow which is definitely worth a visit with a wide range of articles, maps and photos. See John Snow – Historical Giant in Epidemiology

Epidemiology

John Snow is considered a pioneer of modern epidemiological methods. Epidemiology is the study of how often diseases occur in different groups of people and why (more detail here). You can find an epidemiology wall poster providing an overview of common terminologies and methodologies here (looks great in epidemiology department offices, corridors and meeting rooms throughout the world)

Mitch Strachan, a maths teacher from Ohio, USA, John Snow enthusiast and member of the Society has put together a superb set of slides about Dr Snow and the 1854 cholera outbreak in London, which he has kindly donated to the Society’s website for all to enjoy! Click on the link or picture below to download a copy.

The Society

The John Snow Society aims to promote the life and works of Dr John Snow, a pioneer of epidemiological method and celebrated anaesthetist. The Society has over 4,000 members worldwide, many of them eminent specialists in their fields.

As outlined in the Constitution, the Society has a serious intent, publishing news, collecting facts and dates related to the life and works of John Snow and organising the Annual Pumphandle Lecture Series, but it also aims to provide a communication network for epidemiologists and those trained in the Snow tradition throughout the world.

Membership is open to anyone who wishes to celebrate the memory of John Snow. International membership is encouraged, the only requirement being that you visit the John Snow pub – located on the site of the original pump – on any trip to London!

The John Snow Society is based in the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Founders of the Society

Professor Paul Fine, LSHTM, Dr Dilys Morgan, Public Health England, Dr Mary O’Mahony, Former HPA, Dr Ros Stanwell Smith, Royal Society for Public Health/LSHTM and Professor Jimmy Whitworth, LSHTM

Steering Committee

Professor James Hargreaves (Co-chair), Charlotte Flynn (Co-chair), Dr. Lauren D’Mello-Guyett (Co-secretary), Dr. Pedro Hallal (Co-secretary), Professor Paul Fine (Archivist and Broadsheet), Professor Jimmy Whitworth (Social Secretary and Pub liaison officer), Professor Sebastian Funk (Treasurer), Dr. Patrick Nguipdop-Djomo (Co-web content officer), Dr. Seyi Soremekun (Co-web content officer), Professor Alex Mold, Professor Dilys Morgan, Professor George Rutherford, Dr Marta Tufet, William Roberts (ex-officio), Professor Liz Allen (ex-officio)

Constitution

The constitution of the John Snow Society as approved by it’s Members at the Annual General Meeting can be found here: http://www.johnsnowsociety.org/constitution.html

Statement of the JSS on Decolonising Global Health

John Snow was a critical force in the establishment of modern epidemiology. However, epidemiology has many tangled roots. Not all of them lie in Western medicine, and nor do all of them begin with John Snow. The emergence of epidemiology as a discipline in the nineteenth century cannot be separated from its time which was characterised by colonialism, war and slavery.

John Snow is sometimes called the ‘father of epidemiology’, but as a society we recognise this characterisation is inappropriate in a variety of ways. As a Society, we seek to to acknowledge power and privilege; value all forms of knowledge; involve people of colour; be accountable and transparent.

We also celebrate epidemiology’s potential to contribute to a healthier, equitable, and more just world today.